First solo exhibtion: Imagining Science. An interdisciplinary painting exhibition

A research into the study of synthetic thinking, looking and doing in order to investigate the reinvention of painting.

A note on Visual Book

These images are taken from Visual Book, a post-exhibition document published for the exhibition, “Imagining Science. An interdisciplinary painting exhibition. Ng Joon Kiat”, held in Singapore in 2003. Visual Book is an experimentation of replacing catalogue reproduction of paintings with sketches made on computer. Visual Book serves as a catalyst for audiences to make imaginary connections of the paintings in the exhibition.

Statement

Imagining Science. An interdisciplinary painting exhibition

My research is about the study of synthetic thinking, looking and doing in order to investigate the reinvention of painting. What the History of Modernist paintings tried to deal with in its ideas of materiality in painting was, philosophically, just one aspect of the problem of depiction, where the issue of the thinking and doing process is put into question. I have decided to research into this study of synthetic thinking, looking and doing so that I can reconsider this philosophical problem.

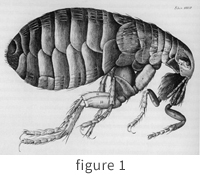

I also reference the history of science, when art and science illustrations were closely associated, in order to find content for my painting. I use the study of the history of biological illustration (figure 1 ), which answers to a “Poussinist” ideal of precision, to form one side of a dialectical equation. In the history of cell biology illustration, I study a variety of descriptive drawing modes, which interpret subjects seen under a microscope. The issue of abstract, subjective thinking in scientific perceptions forms the other side of the dialectic for a synthesis to evolve.

In my paintings, I try to explore a new form of ‘theoria’ and ‘aesthesis” to negotiate a new kind of visual aesthetics. The terms ‘theoria’ and ‘aesthesis’ come from Ruskin’s writing. Peter Fuller2 describes this when he reconsiders the meaning of aesthetics. My exploration of ‘theoria’ and ‘aesthesis’, particularly in biological science, is about finding a ‘Sciart’ aesthetic for my paintings. By ‘Sciart’ aesthetic I mean the amplification and exploration of aesthetic interventions in the interpretation of microscopic visuals. The term ‘Sciart’ was taken from the Wellcome Trust magazine3. The idea of a ‘Sciart’ aesthetic is fascinating because it suggests the possibility of exploring a spiritual dimension in the objectivity of science. A spiritual dimension reflects the need to be humane in urbanized society. Believing in the existence of a ‘Sciart’ aesthetic in my painting is important because then the use of pigment to show physical form becomes more than just painting for the sake of paint, surface and color.

In my studio practice I always use the dialogue-dependent methodology of working. Sometimes, I make object-based works and computer prints as a part of my study for painting. But sometimes, I use it to question the practice of painting. When I begin a new painting, I think about what I have already done and what I can respond to, from previous works. Any painting is always the result of a response to previous artwork. The few layers of paint on canvas, which themselves manifest as visual elements, are always the negotiation ground of the thinking, doing and seeing process. Most of the time, this initial stage of painting is the most problematic part in the whole painting process. This is because what I think I want to see and what I have made do not always match. Therefore, sometimes belief can be more important than seeing. As Merleau-Ponty describes in his book, Phenomenology of Perception4,

‘Objective thought is unaware of the subject of perception. This is because it presents itself with the world ready made, as the setting of every possible event, and treats perception as one of these events.’

As the canvas surfaces build up with paint, some of the initial surfaces are visible and some not. The visibility of a background surface depends on the levels of illusionistic depth I conceived of, from a particular impression of microscopic visuals. I also used visual ideas of drawing in a painterly mode to find synthetic positions between reasoned control and intuitive action. Based on this kind of painting process, I try to introduce paintings with different sets of visual styles but similar conceptual concerns. As Merleau-Ponty describes,

‘Reality is not a crucial appearance underlying the rest, it is the framework of relations with which all appearances tally.’5

NG Joon Kiat

Dated March 2003

Endnotes

1 Joseph G. Gall. A Pictorial History VIEWS OF THE CELL. Baltimore. The American Society For Cell Biology. 1996. Pg 14.2 Peter Fuller. PETER FULLER’S MODERN PAINTERS. Great Britain. Methuen London. 1993. Pg. xxxi. Para. 3.

3 Ken Arnold. Science and art: Symbiosis or just good friends? Wellcome News. Science Art. 2002 Supplement 5. Pg. 3.

4 Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Phenomenology of Perception. London. Routledge. 2002. Pg. 240. Para. 1.

5 Ibid., Pg. 349. Para. 2.