Imagining a Geographical Presence:

A Study of the Horizon in Contemporary Painting

A Solo Exhibition by Ng Joon Kiat

National Museum of Singapore, March 2007

Beyond This Line, We See

The horizon. Infinite possibilities and at the same time, a definitive divide between heaven and earth. A line lying at the end of time, stretching and remolding itself, as far as the eye can see. A line that draws and redraws its latitude with each minute shift in the viewer’s position; it is also a curve that remakes its form with each hour of passing light. Because what we see can only be a part of the perimeter - a topographical line that both helms us in and holds us out - another’s presence can only be implied by the invisible.

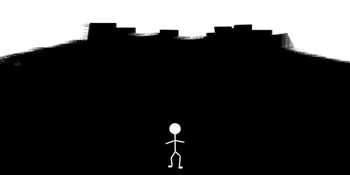

If this horizon is a line that marks the extremity of sight, it is also the jagged edge of a tilted plane upon which we have chosen to site our vantage point (Fig. 1). Hardly surprising then, that the ancients were convinced of earth’s flatness before their ships, loaded with intrepid explorers, began tumbling over the ocean’s edge.

The leitmotif of the plane is one that recurs throughout Ng’s works, most obviously in the Horizontal paintings. Across the stretched canvas surface of Land Series 11 (Fig. 2), we see how a languid brush has left visceral evidence of its play in pools of thick ochre, spreading and dragged over the canvas-covered wood. Viewed in cross-section, its drapery of thick oil paint, pulled down by gravity, manages to conceal only in part the horizontal layers of the cross section before drying in mid-action (Fig. 3).

This deliberate freeze-frame detail allows the edges of oil paint to function as l’agent provocateur in directing the viewer’s gaze, to the contrast between the frozen seep of the oils and the parallel lines of the caked canvas on its angled frame, thus accentuating the evocation of the horizon in the latter.

By the late 1960s, American critic Michael Fried had concluded that painting was “an art on the verge of exhaustion, one in which the range of acceptable solutions to a basic problem – how to organize the surface of the picture – is severely restricted.”1 Since the Renaissance, there has been little change in the shape and form of a painting as a piece of canvas stretched over an angled, usually rectangular, wooden frame. While Renaissance painters like Michelangelo had sought to sublimate the material confines of canvas and paint the painted illusion of a perfect beauty beyond earthly experience, modern artists like Robert Rauschenberg (b. 1925) and Frank Stella (b. 1936) chose instead to challenge the painting’s form directly, by adding collage and found objects to the surface, in an attempt to break down the boundaries between painting and sculpture.

Even so, the area outside the rectangle remains largely unexplored. Jackson Pollock’s (1912 - 1956) action paintings, in their attempt to imprint the energy of the artist directly onto the canvas, might be considered the most adventurous foray thus far. It would almost seem as if any change made to these formal dimensions could potentially undermine a painting’s claim to that category of art known as painting.

Ng’s unusual mode of display is a response to the perceived crisis of painting at this historical juncture, living as we do in the “society of the spectacle,” where the disappearance of art has become its own vanguard.2 To view painting as a physical object of particular and unique dimensions, and not just the design of lines and colors on a flat surface, is a perspective only too easily forgotten in this age of easy reproduction.

It would seem that it is now necessary for the artist to force the re-evaluation of the painting as a deconstructed material object upon his audience, if only to enable us to restart the conceptual journey together, from the same point on a distant horizon, a point coming at “the end of the world of art.”2 In the Oscillation paintings, the repetitive movement of plane sliding over plane is used to draw attention to the painted canvas’s existence in a separate physical dimension from wall that is its background.

Ng’s experimentation in painting and exhibition design updates the historical discourse of painters on painting. By dramatizing the display of works within a conventionalized viewing space and incorporating the audience as participant-spectator, Ng brings in elements of theatre into what might otherwise be a typically static installation of paintings on a national museum’s gallery walls.3 There is some risk, of course, that the paintings in the Horizontal section might be pushed so far out of display conventions that they are seen as installation works instead of paintings on horizontal frames.

This active participation in the design of the exhibition space can also be read as a signal, of the shift in Ng’s role from artist to curator. Instead of allowing the works to negotiate their own terms with the space, Ng consciously tampers with the conditions of display in order to affect the audience’s reading of the works.

How does one learn to look beyond a painting for what it is, without losing sight of what it is? In adjusting the lines of sight, with the installation of the paintings on custom-made horizontal planes instead of on the wall, Ng underscores how the context of display frames the relationship between the work and the viewer. This unconventional mode of display in the Horizontal section offers a conceptual renovation of the classic “white cube,” through the liberation of the painting from its traditional hanging.4

The paintings are understood to be “object(s) in a situation – one that, virtually by definition, includes the beholder,” as opposed to “previous art” where “what is to be had from the work is located strictly within (it).”6 Here, the artist seeks to reconfigure the dynamics of viewing, without undermining the painting as the object of the gaze.

At first glance, the systematic ordering of the works into Oscillation paintings, Horizontal paintings and Drawings appears to simply reveal the artist’s meticulous sense of organization. However, when the initial visual impact of Ng’s extremely tactile works have subsided, we may begin to appreciate the threads of connection between the works and observe the artist’s design of the exhibition as a precisely composed and choreographed performance which allows the works and the audience to interact.

I use the word “choreographed” with the Oscillation paintings foremost in mind, since their manner of installation most effectively introduces the element of time into the exhibition space. On the other hand, the idea of performance is perhaps best illustrated by the storage of the Map Drawings inside the chest of drawers. This latter mode of installation demands the audience’s active participation as performer. The exhibition visitor takes on the role of a welcome intruder who succumbs to the temptation of forbidden secrets when he or she begins to sift through the contents of the invitingly unlocked drawers. Through this exhibition setup, the spectator is co-opted into the act of display and thus shares the responsibility of choosing what is to be seen.

Where and when does a line end? Ng has knitted painted strokes and linear forms into densely layered imaginary maps that overlap and re-map spaces in multiple dimensions. Twining, intersecting, knotting and spinning in space, these painted markings form trail maps of Ng’s thought process. In Map Drawing Series 13, the fine thin baby blue and pale grey acrylic lines run to the very edge of the paper and seem to disappear off the surface. The relaxed mood of these preparatory works is playfully captured in the turquoise circles, orange X symbol and green squares of Map Drawing Series 7, for example, which call to mind the evergreen pen-and-paper game of noughts-and-crosses

(Fig. 4). We can imagine the vibrantly hued lines of the Map Drawings swirling playfully across the handcrafted paper before leaping into air to continue their free form play.

The game continues as these invisible strings, upon contact with the wall, tauten into metal planes that stretch out at an angle like mischievously stuck out tongues. Transfigured into metal, they provide elegantly formal underlines for the paintings in the Horizontal section. These slanted metal bars stretch out like motionless dancers in a balancing pose, palpating with a quiet energy (Fig. 5). As the eye traces the now-solid metal line to its point of contact with the wall, we discover epicenters where the controlled tension of the folds is being transformed into seismic waves that radiate invisibly across the white gallery walls, prompting the Oscillation paintings into an inexorable kinetic swing (Fig. 6).

Planes, both real and illusionary, are ubiquitous in the Map Drawings. Multiple layers emerge and recede from the handmade paper, which act in this context as the anchor dimension for planes in front and towards the back. The different textures of various mediums create the sense of three-dimensional forms and the illusion of depth in Map Drawings Series 7, where Ng’s highly tactile acrylic markings appear only loosely bound to the delicate weave of the handmade paper, as if on a separate layer that can be easily peeled off.

The front plane is distinguished by its sense of solidness, with multi-hued designs, like the charming yellow, pink and blue ribbon-like X motifs in Map Drawing Series 9, having been applied as pure viscous pigment. In Map Drawing Series 11, visual symbols such as squares and loops have been placed in colored formations over delicate nets and neat scribbles. The solidity of these grouped acrylic markings create the illusion of real string and fabric swatches, thus infusing the drawings with a sense of collage.

In other drawings, the Map Drawing Series 1 and 7 for example, Ng has applied fine pearl powder to create an ethereal depth of space. The sprinkled pearl powder imbues certain paper fibers with a light luminescence, giving the impression of a barely perceptible layer of mist receding behind the paper into another dimension, in opposite direction from the forward protrusion of the colorful acrylic lines.

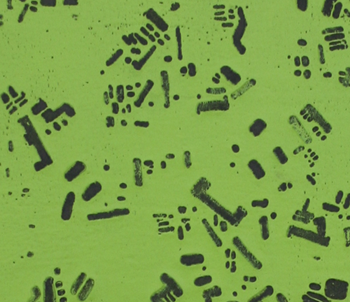

Ng’s conceptual experiments in dimensionality are not limited by the canvas perimeters or by surface conventions. He makes an intriguing comment on the transfiguration of paint from liquid to solid state with Map Drawing Series 14 and 15. These acrylic sketches stand out from the rest of the drawings with their bold green and black patterns on silkscreen cloth. Ng first uses black acrylic paint to design the cloth’s surface, leaving some parts unpainted and the rest to dry into an impermeable waterproof layer (Fig. 7). Green acrylic paint is later applied on the back of the cloth and using a palette knife, Ng then forces the thick paint to permeate through the unpainted parts of cloth, which surfaces and solidifies into a striking pattern.

By compelling the paint to undertake a literal passage through the silkscreen cloth, Ng illustrates how the organic nature of paint as visual substance, through the process of painting, is constantly affected by its own changing physical states as well as its interactions with other elements, whether of cloth, air, or the passing of time.

The Map Drawing Series is a reminder that what we see in works of art, like a map, can only be a topographical guide abstracted from a larger reality.

. . . . .

We are explorers of new territory, sailing in search of new horizons.

We are excavators digging in old ground for long-forgotten human treasures.

In this age of biennales, fancy new media works and spectacular performance art pieces appear to have seized the day. Shaping new visual possibilities from the repetitive motion of putting paint to canvas can sometimes be a tedious process, often eschewed by young artists in a hurry. But the tide is turning, and it has become evident that painting is alive and thriving, and Ng’s work is rich with possibilities for those who can see.5

. . . . .

PhD candidate, Princeton University

18 February 2007

Endnotes

1 Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood,” in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998. p. 153.

2 Debord, Guy. “Negation and Consumption of Culture,” in Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books, 1995.

3 Ibid., p. 135.

4 Fried, Art and Objecthood. Fried’s concern about the “condition of theater” marring the quality of painting through weak synthesis of disparate arts would be voided by Ng’s process since the design of the exhibition space came after the completion of his paintings, without any anticipation of the future audience at the time of production.

5 O’Doherty, Brian. Inside the White Cube: the Ideology of the Gallery Space. Santa Monica, Calif.: Lapis Press, 1986.

6 Fried, Art and Objecthood, pp. 163-5.

7 Strickland, Carol. “East German Expressionism,” in The Christian Science Monitor, September 29, 2006. Things have come full circle, judging from the long waiting lists for Leipzig School virtuoso paintings, a current frenzy jumpstarted by leading contemporary collectors, with none less than the Young British Artists patron Charles Saatchi in their midst. Ironically, it is likely to be painting’s intrinsically anti-trend qualities that make it so very alluring and different for contemporary art connoisseurs weaned on installation and conceptual art works.